How to classify muscle injuries on MRI using the British Athletic Muscle Injury Classification (BAMIC) system

Soft tissue injuries are very common in sport/physical activity and recovery timelines can take anywhere from 10 days – 16 weeks. These timelines are decided using physical assessment and understanding of muscle-tendon complex injury healing but, in the case of lower limb injuries, can be aided with an MRI of the area. The radiologists who interpret the scan results will often use the BAMIC system to identify the area and grade of the injury which can help in determining return to play timelines.

Soft tissue injuries are very common in sport/physical activity and recovery timelines can take anywhere from 10 days – 16 weeks. These timelines are decided using physical assessment and understanding of muscle-tendon complex injury healing but, in the case of lower limb injuries, can be aided with an MRI of the area. The radiologists who interpret the scan results will often use the BAMIC system to identify the area and grade of the injury which can help in determining return to play timelines.

The area is typically divided into three parts of the muscle-tendon complex:

1. Myofascial: Involves the periphery of the muscle, including the surrounding connective tissue layers (epimysium, perimysium, aponeurosis). The myofascial allows force transmission and absorption through the muscle-tendon unit.

2. Myotendinous junction/muscular: A blend of muscle and tendon connection this is potentially the location of greatest force production within the muscle tendon unit.

3. Tendon: The most serious of the three when the central tendon is involved as there are high re-injury rates if the person returns to high level physical activity too early. Tendons take longer to heal than muscle or fascia due to the less vascularity. Also important to note that intra-muscular tendon parts has less sensory neural innervation which means reported pain levels is not a good indicator of severity of injury with those athletes.

Classification system

grade 0a: focal neuromuscular injury with normal MRI

grade 0b: generalised muscle soreness with normal MRI or MRI findings typical of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS)

grade 1 (mild): high STIR signal that is <10% cross-section or longitudinal length <5 cm with <1 cm fibre disruption

grade 2 (moderate): high STIR signal that is 10-50% cross-section; longitudinal length 5-15 cm with <5 cm fibre disruption

grade 3 (extensive): high STIR signal that is >50% cross-section or longitudinal length >15 cm with >5 cm fibre disruption

grade 4: complete tear

Rehabilitation and return to play considerations

The health professional will typically take into account a myriad of factors to get someone back to exercise as quickly (and safely) as possible. These include (but are not limited to):

· Previous injury history

· Physical assessment findings

· Current activity level

· Goals of the patient

· Response to treatment and rehab

· Time of the season (eg finals etc)

Here at East Vic Park, we are experienced in treating soft tissue injuries. Book in to see one of your friendly physiotherapists today.

ITB Syndrome - aka Runner's Knee

Iliotibial band syndrome is a common knee injury and primarily seen in runners. In this blog we will delve into the symptoms, causes and management for ITBS.

What is the Iliotibial Band (ITB)?

The ITB is a tendinous continuation of the tensor fascia latae muscle (TFL). It originates from the side of your hip and runs down the outside of your thigh to insert below the knee.

What is Iliotibial Band Syndome (ITBS)?

ITBS is when the ITB becomes inflamed and irritated due to repetitive rubbing over the outside of your knee. It is common among runners and cyclists and may occurs due to an increase in activity load.

What are the symptoms of ITBS?

Pain on the outside of the knee

Pain aggravated by activities involving bending/straightening the knee: i.e using stairs, going up or down hills, running, cycling

Pain when touching the side of the knee

Feelings of snapping on the outside of the knee during activity

Factors leading to ITBS:

A quick or large increase in load

Training/running form

Increased ankle pronation

Hip drop

Knee valgus

Muscle strength – particularly glutes

Footwear

ITB tightness (note – this is often a symptom caused by the other factors)

Management:

In the early stages the aim of treatment is to reduce the inflammation and avoid provoking the area.

Rest and activity modification: temporarily reducing/avoiding activities that worsen the pain

Ice, elevation and anti-inflammatories

Reduce compression over the lateral knee: avoid stairs, crossing legs, sleeping with legs together

After the pain has settled, it is time to address the factors that have caused the ITBS to occur. This can involve the following aspects:

Footwear

Exercises the strengthen glutes and improve control

Stretching and foam roller – aimed at TFL and ITB attachments to the quads

Graduated return to activity

If you feel you are suffering with iliotibial band syndrome or other knee pain please get in touch with us for a thorough assessment and individualised treatment plan.

Understanding Rotator Cuff-Related Pain

Rotator cuff related pain is a common musculoskeletal condition that affects millions of people worldwide. The rotator cuff consists of a group of four muscles and tendons that stabilize the shoulder joint and allow for a wide range of motion. When these structures become injured or damaged, they can lead to pain, discomfort, and limited mobility. In this blog post, we will delve into the causes, symptoms, acute phase management, and long-term outcomes of rotator cuff related pain.

Introduction:

Rotator cuff related pain is a common musculoskeletal condition that affects millions of people worldwide. The rotator cuff consists of a group of four muscles and tendons that stabilize the shoulder joint and allow for a wide range of motion. When these structures become injured or damaged, they can lead to pain, discomfort, and limited mobility. In this blog post, we will delve into the causes, symptoms, acute phase management, and long-term outcomes of rotator cuff related pain.

Causes:

Overuse and Repetitive Strain: Engaging in repetitive overhead activities such as painting, throwing, or lifting can strain the rotator cuff muscles over time, leading to inflammation and pain.

Trauma or Injury: A fall onto an outstretched arm, direct impact, or sudden force can cause tears or strains in the rotator cuff tendons or muscles.

Age-Related Degeneration: As we age, the blood supply to the tendons decreases, making them more susceptible to degeneration and tears.

Poor Posture: Bad posture can alter the mechanics of the shoulder joint, increasing the risk of impingement and rotator cuff irritation.

Muscle Imbalances: Weakness or imbalances in the muscles surrounding the shoulder can affect the stability of the joint and contribute to pain.

Symptoms:

Pain: Dull, aching, or sharp pain in the shoulder or upper arm, particularly during overhead movements or while sleeping on the affected side.

Limited Range of Motion: Difficulty reaching, lifting, or performing everyday activities that involve shoulder movement.

Weakness: Reduced strength during arm movements and difficulty holding objects.

Clicking or Popping Sensation: Some individuals may experience clicking, popping, or grinding sensations during shoulder movement.

Night Pain: Discomfort and interrupted sleep due to shoulder pain while lying on the affected side.

Acute Phase Management:

Rest from Aggravating Activities: Give your shoulder time to heal by avoiding activities that exacerbate the pain.

Avoid Overhead Activities: Minimize or modify activities that involve repetitive overhead movements.

Ice: Applying ice to the affected area for 15-20 minutes several times a day can help reduce inflammation and alleviate pain.

Pain Management: Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can help manage pain and inflammation, but consult a healthcare professional before use.

Physiotherapy: We can design a tailored exercise program here in the clinic to improve range of motion, strengthen muscles, and correct any imbalances.

Long-Term Outcomes and Management:

Physiotherapy and Exercise: Regular participation in a structured rehabilitation program can lead to improved shoulder function, reduced pain, and enhanced muscle strength.

Posture Correction: Learning proper posture techniques can prevent unnecessary stress on the shoulder joint and reduce the risk of future injuries.

Gradual Return to Activities: As your shoulder heals, gradually reintroduce activities while maintaining proper form and technique to prevent re-injury.

Healthy Lifestyle: Maintaining a healthy weight, staying active, and avoiding smoking can promote overall musculoskeletal health and aid in recovery.

Surgical Intervention: In severe cases where conservative treatments are ineffective, surgical options such as arthroscopic repair may be considered, but should not be the first choice in most cases.

Conclusion:

Rotator cuff related pain can significantly impact daily life, but with proper management and treatment, most individuals can experience complete relief and restored function. Early intervention, adherence to a rehabilitation plan, and lifestyle modifications can contribute to long-term positive outcomes. If you're experiencing shoulder pain, get in touch for a thorough evaluation and personalized guidance on managing your pain.

Patterns of Knee Instability

There are four type of knee instability each characterised by different directional instability based on structures involved.

Anteromedial Instability (AMRI)

Anteromedial instability relates to an unstable to medial knee compartment caused by chronic medical collateral ligament damage/laxity.

The pattern of instability noted is anterior displacement of the medial tibial plateau on the medial femoral condyle. The lateral compartment remains stable unless any ACL ligament involvement.

Anterolateral Instability

Anterolateral instability is associated with ACL ligament injuries. Instability is characterised by a posterior and lateral displacement of the lateral femoral condyle on the tibial plateau.

Posteromedial Instability

Posteromedial instability can be caused by damage to the posterior horn of medial meniscus, superficial and deep fibres of the MCL and the posterior oblique ligament. This type of injury is usually associated with multi-ligamentous injuries.

Posterolateral instability (PLRI)

This pattern of instability is characterised by posterior displacement of the lateral tibial plateau in relation to the lateral femoral condyle. Injury to the posterolateral corner associated with this type of instability. The posterolateral corner consists of the lateral collateral ligament, popliteal ligament and the popliteus tendon complex.

Flexor Hallucis Longus tendon injuries

Flexor Hallucis Longus muscle (and subsequent tendon) runs down the medial border of the tibia past the malleolus and inserts into the plantar surface of the foot and into the base of distal phalanx of hallux. Its role is to move the big toe downwards. FHL pain is usually characterised by medial ankle and foot pain. Sometimes, the discomfort can run up into the medial calf.

What?

Flexor Hallucis Longus muscle (and subsequent tendon) runs down the medial border of the tibia past the malleolus and inserts into the plantar surface of the foot and into the base of distal phalanx of hallux. Its role is to move the big toe downwards. FHL pain is usually characterised by medial ankle and foot pain. Sometimes, the discomfort can run up into the medial calf.

How?

Tendon pain can occur due to an overload or an acute injury causing a tear. Typical activities of overload include running and jumping. It can be irritated in end of range plantarflexion eg calf raise or in a stretch position e.g. knee’s over toes with heel down.

When?

Not necessarily typical of a certain age group. Can commonly be seen in dancers (who spend a lot of time in the aggravating positions mentioned above). Can also be seen in those with calf insufficiencies, either transient or permanent e.g. post-surgery like an Achilles repair or after a traumatic injury like an ankle sprain

How does it resolve?

· Avoiding aggravating positions/activities until it settles

· Progressively building load capacity

What is the treatment?

The focus of treatment is to reduce pain levels and restore the capacity of the tendon. This can be done in a few different ways including:

- Manual therapy (eg muscle massage)

- Taping to offload the tendon

- Exercises to strengthen key areas eg calf

- Implementation of load management strategies (eg mapping out impact activities)

- Voltaren gel wrap at night time

If you would like your injury reviewed by one of our physiotherapists, then don’t hesitate to book an appointment.

Plyometrics: Why Should They be in Your Gym Program?

Plyometric training is when we use exercises to make muscles exert a large amount of force in a short amount of time to improve our power output.

Plyometric exercises like jumping, hopping and landing causes the nervous system to develop reflexes to sudden high-stretch loads, improving the rate and scale of motor unit activation.

Key components of plyometric training are:

Focus on rapid movement between phases of muscle contraction (fast movement)

Typically body weight or light weights only (light weight)

These types of movements produce greater power than concentric only movements as more force is released in the plyometric action. This is because it allows the muscle-tendon complex to store more elastic energy which must be released. If we do these movements slowly, we lose this elastic energy (as heat) and therefore it is not efficient.

Research suggests that stretch-shorten cycle exercises should be implemented at the beginning of a training session (or on a separate day by themselves). This reduces the chance of poor technique due to fatigue and allows the athlete to maximize the velocity of movement.

Examples of plyometric exercises

- Drop jump

- Box jump

- Hopping

- Lateral hop/skater

- Split squat jump

Overall evidence based practice suggests the use of plyometrics with traditional strength training for best performance of an athlete.

Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy Middle to late Rehabilitation

In the early stages of rehabilitation, the focus was acute management and early loading to assist with pain relief and base tendon activation avoiding compressive/provocative positions.

In the middle to early phase the focus is on progressive loading of the tendon, isotonically in initially non-compressive loads but gradually progressing to them.

Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy middle to late Stage Rehabilitation

In the early stages of rehabilitation, the focus was acute management and early loading to assist with pain relief and base tendon activation avoiding compressive/provocative positions.

In the middle to early phase the focus is on progressive loading of the tendon, isotonically in initially non-compressive loads but gradually progressing to them. This involves focus on both concentric and eccentric phase with increased duration through each, to increase the time under tension. Eccentric exercises such as Nordics represent low compressive loads progressing to more compressive loading with the Romanian deadlift from double to single leg.

Examples of middle stage exercises from non-compressive to compressive loads include:

Nordic

Single Leg Hip Thruster

Barbell Romanian Deadlift

Single Leg Romanian Deadlift

Late Stage Rehabilitation

The aim of late stage is the involvement of running based technique, stretch shortening cycles and running. If technical deficits in running have been identified, such as longer stride length, then these can be incorporated to not only load the hamstring tendon but also retrain running patterns.

Explosive Step Up

Barbell Walking Lunge

A Skip

Syndesmosis sprains : The high ankle injury

You may have heard various athletes suffering a high ankle sprain or injuring their syndesmosis. But what exactly is a syndesmosis injury? And how does it differ to a normal lateral ankle sprain?

The ankle syndesmosis is the joint between the distal (lowest aspect) of your tibia and fibula. It is comprised by three main supporting ligamentous structures – The Anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, Posterior inferior Tibiofibular ligament, and interosseous membrane (see Figure 1). The role of the syndesmosis is to provide stability to the tibia and fibula and resist separation of these two bones during weightbearing tasks. It also plays a role in assisting with mobility of the ankle.

You may have heard various athletes suffering a high ankle sprain or injuring their syndesmosis. But what exactly is a syndesmosis injury? And how does it differ to a normal lateral ankle sprain?

The ankle syndesmosis is the joint between the distal (lowest aspect) of your tibia and fibula. It is comprised by three main supporting ligamentous structures – The anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, and interosseous membrane (see Figure 1). The role of the syndesmosis is to provide stability to the tibia and fibula and resist separation of these two bones during weightbearing tasks. It also plays a role in assisting with mobility of the ankle.

How does it differ to a common ankle sprain?

Generally, a lateral ankle sprain is a result of and inversion injury and will result in an injury to the outside ligaments of your ankle (ATFL, CFL, PTFL). These ligaments are positioned slightly lower than the syndesmosis and provide stability to the true ankle joint.

Mechanisms of injury:

The most common mechanism for injuring your syndesmosis is a forced dorsiflexion combined with an Eversion movement. Essentially the foot/ankle moves in an upward direction and to the outside of the leg (See figure 3).

The syndesmosis can also be injured with a typical inversion or lateral ankle sprain (Figure 2) mechanism. This usually occurs when the incident is of high force and will result with an injury to the lateral ligaments as well.

Signs and symptoms:

· Mechanism of injury consistent with a syndesmosis injury (forced dorsiflexion + Eversion)

· Pain location may extend above the ankle and into the lower shin

· Swelling may sit slightly above the cease line of the ankle joint

· Difficulty weightbearing, particularly when the foot is in dorsiflexion (knee over toe)

· Low confidence/feeling of instability

Gradings:

Grade 1: isolated injury to the AITFL

Grade 2: Injury to the AITFL and interosseous membrane

Grade 3: Injury to the AITFL, interosseous membrane and PITFL

Grade 4: Injury to the AITFL, interosseous membrane, PITFL and deltoid ligament

Immediate management:

As always if you have recently suffered an injury, please seek medical attention from your physio or doctor for accurate diagnosis and management.

If a syndesmosis injury is suspected acute management will initially involve offloading and protecting the tissues. This may be in the form of one or a combination of crutches, a cam walker (moon) boot and strapping.

Your physio or Doctor may also refer you for imaging such as an x-ray or MRI to assist with diagnosis and understanding the severity of the injury.

Following the acute period of offloading and protection a period of rehabilitation will be required to restore normal function of the foot and ankle. In more severe cases surgery may be required to stabilise the syndesmosis and therefore rehab will commence following a period of protection post-surgery.

If you have experienced an ankle sprain yourself, please book in with one of our physiotherapists for an individualised rehabiltation program.

COMMON ADOLESCENT CONDITIONS – PART TWO: KNEE

Part two of load related adolescent conditions focuses on the knee.

Osgood-Schlatters Disease

What?

An irritation of the insertion of the patella tendon into the tibia. This differs from adult patella tendinopathy due to the immaturity of the adolescent skeleton which means it affects the actively remodelling trabecular metaphyseal bone.

How?

It is usually due to the area’s inability to deal with an increase in activity (particularly activity that uses that area eg running or jumping sports). It can also be related to growth spurts which puts increased tension through the muscles and therefore tendons.

When?

More common in boys and usually between the ages of 10-15 compared with girls which is usually between the ages of 8-13.

How does it resolve?

Usually self resolves with time (6-24 months) however the reason it’s best to seek treatment/advice is due to the pain that accompanies the condition which can affect sports performance and most importantly day to day activities.

What is the treatment?

The main focus of treatment is to reduce pain levels. This can be done in a few different ways including:

- Manual therapy (eg muscle massage)

- Taping to offload the tendon

- Exercises to strengthen key areas

- Implementation of load management strategies (eg RPE scale)

- Advice regarding recovery (eg icing)

The main takeaways about the condition are:

- The adolescent will grow out of it

- It can still be quite painful so there should be a focus on pain relief

- Load management with guidance from a physiotherapist can allow the continued participation in sport without compromising day to day function

If you would like your injury reviewed by one of our physiotherapists, then don’t hesitate to book an appointment. All of our physiotherapists specialise in sport and have had extensive experience with adolescent athletes.

Bowel and bladder health and Pelvic Floor Muscle Dysfunction

The pelvic floor consists of bone, ligament and muscular structures which all work to support internals organ, control bladder and bowel functions as well as assist in reproductive function.

30% of women experience pelvic floor dysfunction including pelvic pain, prolapse, stress incontinence (leaking), urgency incontinence, and frequency incontinence.

Risk factors for developing Pelvic Floor Muscle Dysfunction

- Age

- Pregnancy + childbirth

- Pelvic floor injury

- Increased abdominal pressure

- Intense physical effort

- Constipation

- Obesity

- History of lower back pain

Some of these factors are more controllable than others so it’s best to ensure we are putting our best foot forward with those that we can change. Good bowel and bladder habits are the easiest to change.

- Bowel habits:

- Use of a squatty potty (posture involving chest forward with knees higher than hips)

- No breath holding

- Avoid straining/constipation

- Ensure adequate fibre

- Bladder habits

- Fluid intake 2-3L/day

- Voiding every 2-3 hours,

- Avoiding fluids 2 hours before bed

- Reducing alcohol/diuretics

Hagen S, Elders A, Stratton S, Sergenson N, Bugge C, Dean S et al. Effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training with and without electromyographic biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women: multicentre randomised controlled trial BMJ 2020; 371 :m3719 doi:10.1136/bmj.m3719

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)

Are you unable to recover between training sessions? Experiencing severe wide-spread muscle ache/DOMS? As a female athlete, has your menstruation ever been affected by your training? These can all be signs of energy deficiency and overtraining. Our blog explores what energy deficiency is, how to identify it and how to treat it.

Are you unable to recover between training sessions? Experiencing severe wide-spread muscle ache/DOMS? As a female athlete, has your menstruation ever been affected by your training? These can all be signs of energy deficiencies and overtraining. Our blog explores what energy deficiency is, how to identify it and how to treat it.

What is RED-S?

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (or RED-S) is due to low energy availability in athletes. This means the fuel going into the body from food is less than the energy burnt during exercise. This energy balance should be at least equal and is additional to the normal calories consumed during the day. When energy input is at a deficit, RED-S can have significant impact on many body systems, affecting both injury risk and performance.

RED-S used to be known as the ‘female athlete triad,’ terminology which is no longer used as it affects ALL athletes. The most well-known consequences of poor energy availability are bone stress injury and female athletes losing their period. These are both extreme consequences of RED-S, however there are much earlier signs and symptoms which are lesser known.

Signs and Symptoms

· Poor sporting performance

· Inability to recovery between sessions

· Poor wound healing

· Regular cold and flu sickness

· Irregular/cessation of menstruation/periods (see below; ‘The female athlete’)

· Poor bone health/osteopenia/bone stress response

· Mood changes

· Iron deficiency

· Arrythmias (in severe cases)

Why does it matter?

1. Adverse effect on performance

· Quicker onset of fatigue from less energy available to skeletal muscles

· Reduction in muscle strength/size due to impaired testosterone production and compromised neuromuscular control

· Impaired recovery increasing the risk of overtraining

2. Impact on health and wellbeing

· Increased the risk of chronic fatigue

· Low energy availability decreases the ability to heal from injury. Strains, sprains, cuts and bone injuries will take longer to heal

· Impaired growth and development from inadequate cell turnover

The good news is most effects of RED-S are reversible if picked up early.

Athletes are often worried increasing food intake can result in weight gain. This is not the case for most athletes. Nutritionists and sports science professionals understand the energy demands of sport and ensure the balance between energy input and output is correct.

The female athlete

1. Menstruation

If an athlete has low energy availability, their body is unable to produce normal levels of hormones. This can affect the menstrual cycle in female athletes. Periods may become irregular, or even cease altogether. Although the female menstrual cycle is variable between individuals, an individual’s cycle should be quite consistent. Irregularity or cessation of periods for longer than 6 months, or not getting a period by 16 years of age should be reviewed by a doctor.

2. Contraception

Female athletes may be advised the oral contraceptive pill can treat symptoms and normalise their menstrual cycle. The combined pill produces a synthetic estrogen the body can not process and therefore does not assist with improving bone health. This can mask hormonal problems, without assisting in bone health. Athletes using contraception that contains estrogen may also be screened for risk factors of RED-S. Athletes using contraception that alters the normal production of a period (e.g. Mirena, Implanon) must also be monitored for RED-S symptoms.

How can physio help?

Physios can help review your training program and lifestyle to assess energy availability. If an athlete is at significant risk of RED-S, a Sports Physician should be involved to identify any hormonal/nutritional deficiencies and directly address them. This is commonly done through a blood test.

After any nutritional deficits have been addressed, a physio can help modify training loads and aid with recovery techniques.

Who else can help?

Sports doctor – Vital for initial diagnosis and hormonal/nutritional testing. Depending on severity, medical intervention may be needed (e.g. iron infusion)

Nutritionist – Eat the right food… and enough food, is vital for good energy availability

Strength and conditioning coach – Clever programming results in efficient training and decreases the risk of overtraining.

Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy and Early Stage Rehabilitation Exercises

Proximal hamstring tendinopathy occurs due to an overload of the hamstring tendon inserting into the buttock bone, the ischial tuberosity. It is quite common in runners also in sports/activities which require repetitive tension on the hamstrings plus increased forward trunk lean.

It’s caused by a sudden change in volume, frequency or intensity of exercises, or exposed to high compressive loads such as hill walking/running or forward lean position. Both these activities increased the strain on the proximal tendon. Running technique plays a major role, including an increased stride length or trunk lean puts increased tension on the tendon combined with any major changes in running load.

Much like other tendinopathies of the patella and achilles, pain can initially come on with running then have a ‘warm up’ effect, then return post activity with stiffness the following morning. In more severe cases pain comes on during the run and remains throughout.

Assessment is performed through progressive loading of the hamstring tendon to reproduce pain, in addition to palpation over the tendon. Ruling out other diagnosis such as involvement of the lumbar spine and sciatic nerve involvement are important.

Treatment is aimed at load modification, but just as importantly performing progressive targeted, non-compressive loading of the tendon to enhance its tolerance to load. This starts off with isometrics, dependent on the patient’s irritability but then progressing towards gym-based strengthening and sports specific exercises.

With respect to running, working on reduce stride length, increasing cadence and avoiding hills will assist with reducing stress on the tendon.

Early stage isometric exercises include: 5 reps, 30-45 seconds hold and can be performed daily prior and post runs. These also act as ‘panadol’ to assist with pain relief.

Single Leg Bridge Hold

Prone Hamstring Curl Isometric

Early Stage Ankle Sprain Rehabilitation

Ankle sprains are one of the most common lower limb injuries reported by active individuals, with a high reoccurrence rate. The lateral ligaments (outside of the ankle) are the most commonly injured, as discussed in one of our previous blogs as seen here https://www.eastvicparkphysiotherapy.com.au/news/2021/1/14/chronic-ankle-instability

Injury prevention and rehabilitation is an effective way to reduce the risk of post injury recurrence.

Key areas of a rehab plan include the following

Restoring full range of movement

Restoring range of motion is important in the initial stages of rehab, this can be achieved by correct heel toe walking (if needed with the assistance of crutches dependant on severity of injury). These exercises are used in the beginning phase of rehabilitation

Ankle Active range of motion

- Ankle Alphabets

- Ankle Pumps

- Calf Stretching

Pain free stationary cycling is also a great way to progress active range of motion exercises as well as re introducing a cardiovascular component to the program.

Muscle Strength

Strength needs to be addressed in all directions available in the ankle. These include dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, inversion, eversion. To increase the difficulty of these movements, your physiotherapist may use external resistance, such as therabands, or using your own body weight, through calf raise exercise. Body weight exercises are encouraged as soon as the injury is pain free.

Proprioception

Proprioception is the awareness of joint position and movement, and this becomes impaired after a ligament injury. It is an important part of ankle injury rehabilitation and can start early in your program. Examples of proprioception exercises include:

- Standing on one leg

- Balance Boards

The above exercises are only a guide and will need to be progressed to ensure a full recovery. If you have experienced an ankle sprain please book in with one of our physiotherapists to have your rehabilitation individualised to suit your needs.

Common Return to Play Tests

A big focus of returning to activity post injury is reducing the risk of recurrence. As a physiotherapist, we can somewhat measure the risk via tests which give us values that we can A: compare to the uninjured side or B: compare to normative data that has been collated through research.

A big focus of returning to activity post injury is reducing the risk of recurrence. As a physiotherapist, we can somewhat measure the risk via tests which give us values that we can A: compare to the uninjured side or B: compare to normative data that has been collated through research.

Below is a list of common “return to play” (RTP) tests which are utilised in rehabilitation post injury to inform the athlete/patient of their progress and readiness to return to normal activity.

1. Triple hop test

This test involves performing three consecutive hops in a straight line to achieve maximum distance from the starting position. This is a very useful test to measure repetitive power output as it involves maintaining explosiveness over three events rather than just one. Typically, the aim is to be within 10% distance of the uninjured side. However, there is preference (more in an elite sporting environment) that if you have the athletes baseline score, that should be the aim. If unsure of the baseline for the athlete, you can potentially use the normative values for college students which is; Female 4.28m (give or take 54 cm) and Male 5.83m (give or take 72cm).

2. Athletic shoulder (ASH) test

This is a relatively new test (2018) that focuses on isometric force production in 3 different shoulder positions. The patient/athlete lies on their stomach and pushes into a force production measuring device (eg Hand held dynamometer). This test is theorised to be useful for contact or overhead sports. Again typically you are looking for a difference of no more than 10% of the uninjured side. Gold standard would be comparing the athletes/patients baseline to their current scores.

3. Single leg squat (maximum repetitions)

This test has been around since 2002 and as an exercise before that (1998). As a test, it is used to identify movement dysfunctions like pelvic un-leveling, valgus overstrain at the knee and subtalar hyper-pronation. There is variability in the description of how to perform the test between research articles. In this example from the Melbourne ACL Rehabilitation guide, the test is called a single leg rise test and is performed by:

- Standing on one leg and having the other foot off the ground

- Sitting back to lightly touch the surface behind you which is set to 90 degrees knee and hip flexion

- Having arms crossed over chest

- Repeating for as many times as form is acceptable at a tempo of 2 seconds up and 2 seconds down

The main aims for this particular test (single leg rise) is to evaluate trunk control, hip abduction isometric strength, quad muscle eccentric control endurance and single leg balance. The test is to fatigue with normative data suggesting repetitions greater than 22 can reduce risk of re-injury. Again, a difference of no more than 10% side to side is ideal.

If you are returning from an injury and would like to be tested for readiness to return to play then book an appointment with our physiotherapists today.

Low Back Pain Myths

There is a lot of information out there on low back pain and injuries. Some of which is very useful but on the other hand there is a lot of misinformation which can sometimes lead us in the wrong direction. In this blog we will look to debunk some of the most common low back pain myths!

There is a lot of information out there on low back pain and injuries. Some of which is very useful but on the other hand there is a lot of misinformation which can sometimes lead us in the wrong direction. In this blog we will look to debunk some of the most common low back pain myths!

Myth # 1 : I Should brace my core or I will get pain

This is a very common thought and is a big reason why people seek help for their low back. Although we have previously thought bracing can help relieve symptoms it can in fact increase the forces going through the back and in some cases lead to pain. The muscles around the trunk play an import role in movement and stability but trying to actively brace these muscles can often lead to stiffness and inefficient movements. The body is clever, our trunk muscles will naturally contract and work when required to assist in tasks such as lifting.

Myth # 2: My low back pain is cause by my back/pelvis being out

One of the most common myths when it comes to low back pain. The back is extremely strong and robust and without serious trauma or force the back and pelvis does not go ‘out’. Manual therapy techniques such as manipulations and adjustments DO NOT put these structures back in to place but they can however provide pain relief which is helpful in the short term.

Myth # 3: I have a disc bulge and degeneration and that is causing my pain

Disc bulges and degeneration are very common and have a high occurrence rate amongst people who don’t have low back pain. We consider these changes to be age related and are not necessarily linked to pain. Approximately 30% of people in their 20’s will have a disc bulge in the absence of low back pain and this percentage goes up approximately 10% for every decade in life. Further to that disc bulges and protrusions have shown to recover on imaging over time. So, it is likely that a disc bulge that you may have previously had is no longer there!

Myth # 4 I need to stand and sit in “good” posture, or I will get pain

There is no such thing as good or correct posture! Despite what we have previously thought and what we may have been told as kids. Research has showed us that there is no direct link to how we sit and stand and pain. Instead, it is recommended to find a posture that you are comfortable with. This may differ from person to person but that is okay. Of course, it is always recommended to keep moving, so taking regular breaks to move around may help reduce the occurrence of discomfort from prolonged positions.

Myth # 5 Bending your back when lifting is bad for your back and you should lift with my knees

The spine holds some very important structures, and it would be a big design flaw if the back was not robust and strong to protect them. In fact, it is one of the strongest parts of the body and can handle large forces. When trained correctly the spine can comfortably handle loads in positions of lifting, squatting and twisting. We are often told to avoid bending the back when lifting however this can often create problems such as inefficient movements and fear avoidance. Like all activities, we need to exposure our body to them for us to get better at it!

Our physiotherapists at East Vic Park Physiotherapy can help answer all your low back related questions. If you would like more information or help with your low back do not hesitate to get in touch!

The Rotator Cuff – Team work at its best

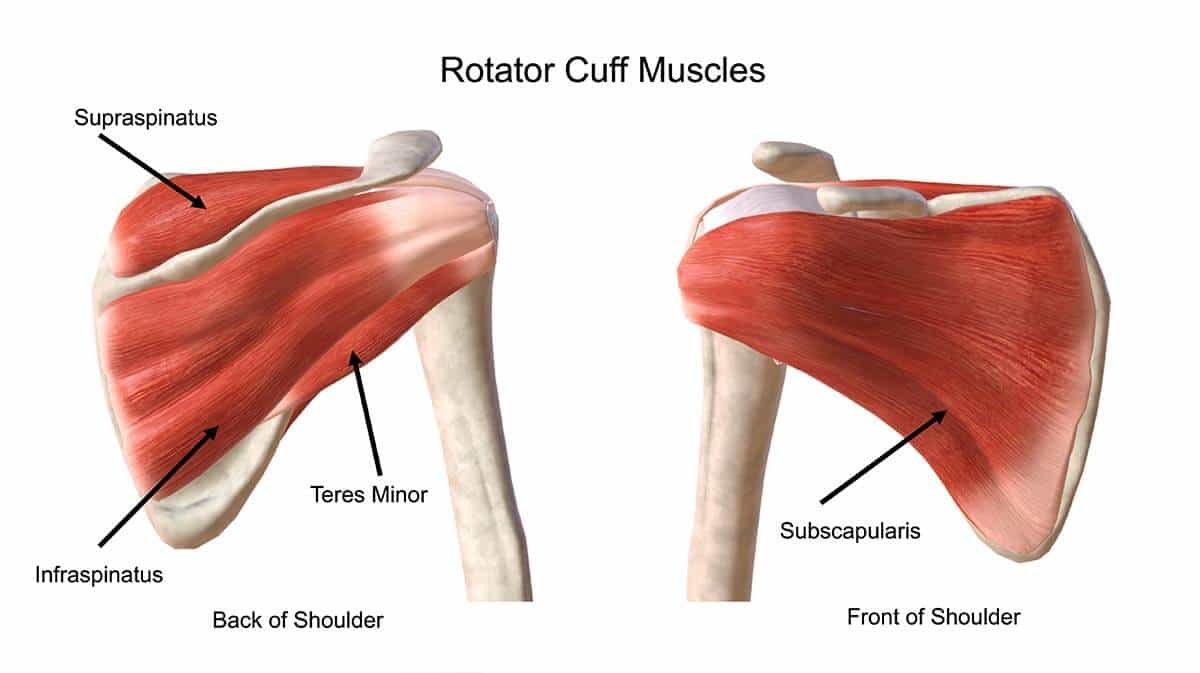

The rotator cuff are a group of four muscles which provide stabilisation of the shoulder (glenohumeral) joint during movement. These muscles include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and the subscapularis.

The rotator cuff are a group of four muscles which provide stabilisation of the shoulder (glenohumeral) joint during movement. These muscles include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and the subscapularis.

The supraspinatus is involved in abduction of the arm (raising to the side), infraspinatus and teres minor external rotation of the shoulder and subscapularis internal rotation of the shoulder. Although Individually these muscles act differently, they provide the combined effect in balancing forces which assist with centering the head of the humerus within the socket and providing a compressive and thus stabilising force with co-contraction when using the arm. It assists the static the shoulder ligaments and labrum to provide overall stability to the mobile joint.

The Rotator Cuff Cable and Crescent

The rotator cuff cable is a key feature of the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff cable helps protect the rotator crescent. The rotator crescent represents the insertional fibres in the shoulder of both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. Tears occur most commonly in the rotator crescent.

This region is protected by the rotator cable, which facilitates a transfer of load if any region of the rotator crescent is damaged, provided the rotator cable remains intact, thus ongoing function of the rotator cuff.

There are many instances where people have had scans of their shoulders, shown rotator cuff tears, but haven’t had traumatic incidents. These findings are quite common in people whom are asymptomatic, but also the protective mechanism of the rotator cable permits the ongoing rotator cuff function in the presence of a tear.

The presence of a rotator cuff tear on a scan is only one element of the patient’s presentation and therefore forms only one part of the assessment findings, which must also match the Physiotherapist’s assessment physical findings before a diagnosis can be delivered.

Costochondritis - A real pain in the chest

There can be many medical reasons for chest, rib and upper back pain including heart and lung conditions, infections and trauma incidences like fractures.

However, once that has been ruled out a diagnosis to be considered is costochondritis.

The condition is classified as inflammation of the costochondral junction of the ribs (where the bone and cartilage meet) or of the costosternal joints (where the ribs connect to the chest bone). The issue is normally unilateral (one sided) but can sometimes be bilateral.

There can be many medical reasons for chest, rib and upper back pain including heart and lung conditions, infections and trauma incidences like fractures.

However, once that has been ruled out a diagnosis to be considered is costochondritis.

What?

The condition is classified as inflammation of the costochondral junction of the ribs (where the bone and cartilage meet) or of the costosternal joints (where the ribs connect to the chest bone). The issue is normally unilateral (one sided) but can sometimes be bilateral.

Signs and symptoms:

- Chest pain that can radiate into the upper chest near the shoulder, down the rib into the area under the armpit and even into the back near your shoulder blade

- Pain can be sharp with certain movements and a dull ache at rest

- Sometimes there is visible swelling over rib joints

- Neck and shoulder range can be affected

- Pain with laughing, coughing, sneezing and deep breathing

Why?

The exact reason for an individual developing inflammation of that particular area is yet to be determined. However, there are a few mechanisms that have been anecdotally found to trigger costochondritis symptoms including:

- Trauma to the area (eg. Direct fall/pressure or injury to the pec muscle)

- Intense exercise of the area

- A bout of illness with lots of coughing

Diagnosis methods

The condition is primarily diagnosed with clinical tests including:

- Palpation of the costochondral and costosternal joints (usually ribs 2-5)

- Assessment of thoracic, cervical and glenohumeral joint range

- Cough/sneeze/laugh test

- Deep breathing test

Scans would only be beneficial if you needed to rule out any of the below alternate diagnoses. Potentially a blood test would be beneficial if a multi joint inflammatory condition is suspected.

Examples of differential diagnosis

- Coronary artery disease (or other heart conditions acute or chronic)

- Pulmonary embolism or pneumothorax

- Rib fractures or subluxations

- Costovertebral sprain

- Tietze syndrome

- Pectoralis muscle injury

- Infections (e.g., pneumonia)

- Xiphoidalgia

Treatment

- A review with a physiotherapist can be helpful to accurately diagnose

- Ice over the joints or heat over the muscles

- Speak to your pharmacist regarding pain relieving medication

- Modification of aggravating activities

- Gentle massage to the neck, shoulder and chest muscles can be helpful in some cases

- Gentle stretches and strengthening exercises once the pain has reduced

If you believe you are suffering from costochondritis then book an appointment to see one of our friendly physiotherapists today!

Knee osteoarthritis: is it as debilitating as we think?

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the result of wear and tear of the joint cartilage. It can result in pain and stiffness when loading a joint. But is OA always a sign we need to protect our joints and stop certain activities? The answer may surprise you.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the result of wear and tear of the joint cartilage. It can result in pain and stiffness when loading a joint. But is OA always a sign we need to protect our joints and stop certain activities? The answer may surprise you.

What is OA?

Osteoarthritis is a break-down of the cartilage in our joints. It mostly affects weightbearing joints such as hips and knees and these joints are subject to larger forces. It was previously thought that joints with OA were to be ‘protected’ by limiting how much we bend, move and load them. We now know this is not true – in fact exercise is one of the most effective ways of reducing osteoarthritic pain.

Knees in particular appear to have many connotations around them and it is widely (but incorrectly) thought that exercise is harmful to our knees. In fact it is quite the opposite – weight bearing exercise helps bone, muscles and other soft tissue adapt to make our knees stronger and more robust. This means an improvement in joint range of motion, muscle length and strength and functional capacity.

How much value should you place on a scan?

It is also important to know that while a scan may show significant osteoarthritic findings, this certainly does not correlate to pain, function or quality of life! Even with ‘severe’ osteoarthritic findings on a scan, very positive functional outcomes can be seen with the above program.

What will help?

The latest guidelines around osteoarthritis, show the most effective way to slow the progression of the pathology is to perform regular weight bearing, strength based exercise. There is good evidence to say this can also significantly reduce pain and improve function. Anti-inflammatories may also help pain and swelling, however you should always consult your doctor before using medication.

It is recommended to perform land based strength exercises 2-3x weekly, such as squats, steps up or leg press. The sets, reps and weight will initially be determined by strength, function and pain levels. This is nicely complimented by aerobic exercises such as walking, bike riding or pool based exercise, although aerobic exercise is not shown to have the same benefit as land-based strengthening.

Our physiotherapists can create a knee strengthening program you can perform at home, all tailored to your individual goals and ability.

Chronic Ankle Instability

Ankle inversion injuries, commonly known as a rolled ankle, are prevalent in court sports such as basketball, netball and tennis and field sports including AFL football and soccer. They affect the lateral ligament complex, which is important for stabilising the ankle joint.

Chronic Ankle Instability

Ankle inversion injuries, commonly known as a rolled ankle, are prevalent in court sports such as basketball, netball and tennis and field sports including AFL football and soccer. They affect the lateral ligament complex, which is important for stabilising the ankle joint.

The lateral ligament complex consists of the anterior talofibular (ATFL), calcaneofibular (CFL) and posterior talofibular ligaments (PTFL). The most commonly affected ligament is the ATFL. In more severe injuries, the CFL and PTFL are affected.

Common mechanisms of injury include landing, stepping on another play’s foot or change of direction.

Although acute ankle injuries are initially managed with ice, compression, rest and taping, many people suffer from ongoing issues such as ongoing pain, swelling, joint instability and recurrent sprains which impact on sport performance. Risk factors for recurrent ankle issues include a previous sprain, insufficient rehabilitation and earlier than recommended return to sport.

Chronic ankle instability (CAI) describes the ongoing limitations following an acute ankle sprain, including ankle instability during load bearing activities and perceptions of your ankle giving way.

In a systematic review by Doherty et al 2013, they found that upto 40% of intial ankle sprains will develop chronic instability within the 12 months following an injury.

Treatment and Prevention

Firstly, its important to identify any risk factors including muscle strength deficiencies, static and dynamic balance deficits or any structural issues. This is performed using functional assessments which consist of a number of ankle specific tasks including balance and various hopping drills to asses the extent of instability.

Following assessment, the implementation of an appropriate rehabilitation program addressing any identified deficits in balance and muscle strength with the aim of progressing to sport specific movements to ensure a safe return to sport. Once returned to sport, performing maintenance strengthening exercises will assist with reducing the risk of re-injury. Taping has also shown to be beneficial in reducing the risk of re-injury, with effectiveness increased with a concurrent preventitive exercise program.

If you are having persistent ankle pain or stability issues during sport or daily life, book in with us for a thorough assessment and plan.

References

1. Doherty C, Delahunt E, Caulfield B, Hertel J, Ryan J, Bleakley C. The incidence and prevalence of ankle sprain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies. SPORTS MED [internet]. 2013[cited 2020 Nov 10];44(1):123-140. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0102-5.

The PLC (PosteroLateral Corner) Injury

The PosteroLateral Corner describes 3 main structures at the back and outside corner of the knee that are important for stabilisation. These resist against hyperextension and rotational forces.

PosteroLateral Corner (PLC)

What is the PLC?

The PosteroLateral Corner describes 3 main structures at the back and outside corner of the knee that are important for stabilisation. These resist against hyperextension and rotational forces. These structures include the;

1. Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

2. Popliteal Fibular Ligament (PFL)

3. PopLiteus Tendon (PLT)

Also, the Posterolateral Capsule.

How did I get a PLC injury?

Risk factors and causes of a PLC injury can vary, including;

o Common sports/scenarios; Football, rugby, soccer, high impact motor vehicle accident (MVA).

o Common concomitant injuries: Occur at the same time as Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) and Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) injuries.

Where does it hurt?

Do you have pain and/or instability at the back and outside of the knee around the joint line? Is there pain AND clicking or crunching?

Note: A noisy knee without pain isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Do I need a scan of my knee?

Likely Yes.

In most cases this a physiotherapist will be able to clinically diagnose a PLC and/or other injuries. If there is concern for damage to the cruciate ligaments or posterolateral corner ligament injuries of the knee then you will likely be referred to a GP or Sports Physician for either an X-ray to rule out fracture and/or MRI to confirm PLC injury. Moderate to high grade injuries will likely require onward referral to a surgeon.

What is my prognosis?

Low and moderate grade injuries often have a good prognosis with physiotherapy guidance.

Higher grade injuries may have difficulty returning to change of direction sports within 6 months and upwards of 12 months if there is a cruciate injury.

What will rehab involve?

Early management will include bracing of the knee, proprioception, strength and non-weight bearing cardiovascular exercise such as gentle swimming and cycling.

Longer term rehab will be dependent on the needs of your daily activities or sport requirements.

Talk to your physio about how to get you back on top of your game!