Low Back Pain Myths

There is a lot of information out there on low back pain and injuries. Some of which is very useful but on the other hand there is a lot of misinformation which can sometimes lead us in the wrong direction. In this blog we will look to debunk some of the most common low back pain myths!

There is a lot of information out there on low back pain and injuries. Some of which is very useful but on the other hand there is a lot of misinformation which can sometimes lead us in the wrong direction. In this blog we will look to debunk some of the most common low back pain myths!

Myth # 1 : I Should brace my core or I will get pain

This is a very common thought and is a big reason why people seek help for their low back. Although we have previously thought bracing can help relieve symptoms it can in fact increase the forces going through the back and in some cases lead to pain. The muscles around the trunk play an import role in movement and stability but trying to actively brace these muscles can often lead to stiffness and inefficient movements. The body is clever, our trunk muscles will naturally contract and work when required to assist in tasks such as lifting.

Myth # 2: My low back pain is cause by my back/pelvis being out

One of the most common myths when it comes to low back pain. The back is extremely strong and robust and without serious trauma or force the back and pelvis does not go ‘out’. Manual therapy techniques such as manipulations and adjustments DO NOT put these structures back in to place but they can however provide pain relief which is helpful in the short term.

Myth # 3: I have a disc bulge and degeneration and that is causing my pain

Disc bulges and degeneration are very common and have a high occurrence rate amongst people who don’t have low back pain. We consider these changes to be age related and are not necessarily linked to pain. Approximately 30% of people in their 20’s will have a disc bulge in the absence of low back pain and this percentage goes up approximately 10% for every decade in life. Further to that disc bulges and protrusions have shown to recover on imaging over time. So, it is likely that a disc bulge that you may have previously had is no longer there!

Myth # 4 I need to stand and sit in “good” posture, or I will get pain

There is no such thing as good or correct posture! Despite what we have previously thought and what we may have been told as kids. Research has showed us that there is no direct link to how we sit and stand and pain. Instead, it is recommended to find a posture that you are comfortable with. This may differ from person to person but that is okay. Of course, it is always recommended to keep moving, so taking regular breaks to move around may help reduce the occurrence of discomfort from prolonged positions.

Myth # 5 Bending your back when lifting is bad for your back and you should lift with my knees

The spine holds some very important structures, and it would be a big design flaw if the back was not robust and strong to protect them. In fact, it is one of the strongest parts of the body and can handle large forces. When trained correctly the spine can comfortably handle loads in positions of lifting, squatting and twisting. We are often told to avoid bending the back when lifting however this can often create problems such as inefficient movements and fear avoidance. Like all activities, we need to exposure our body to them for us to get better at it!

Our physiotherapists at East Vic Park Physiotherapy can help answer all your low back related questions. If you would like more information or help with your low back do not hesitate to get in touch!

The PLC (PosteroLateral Corner) Injury

The PosteroLateral Corner describes 3 main structures at the back and outside corner of the knee that are important for stabilisation. These resist against hyperextension and rotational forces.

PosteroLateral Corner (PLC)

What is the PLC?

The PosteroLateral Corner describes 3 main structures at the back and outside corner of the knee that are important for stabilisation. These resist against hyperextension and rotational forces. These structures include the;

1. Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

2. Popliteal Fibular Ligament (PFL)

3. PopLiteus Tendon (PLT)

Also, the Posterolateral Capsule.

How did I get a PLC injury?

Risk factors and causes of a PLC injury can vary, including;

o Common sports/scenarios; Football, rugby, soccer, high impact motor vehicle accident (MVA).

o Common concomitant injuries: Occur at the same time as Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) and Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) injuries.

Where does it hurt?

Do you have pain and/or instability at the back and outside of the knee around the joint line? Is there pain AND clicking or crunching?

Note: A noisy knee without pain isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Do I need a scan of my knee?

Likely Yes.

In most cases this a physiotherapist will be able to clinically diagnose a PLC and/or other injuries. If there is concern for damage to the cruciate ligaments or posterolateral corner ligament injuries of the knee then you will likely be referred to a GP or Sports Physician for either an X-ray to rule out fracture and/or MRI to confirm PLC injury. Moderate to high grade injuries will likely require onward referral to a surgeon.

What is my prognosis?

Low and moderate grade injuries often have a good prognosis with physiotherapy guidance.

Higher grade injuries may have difficulty returning to change of direction sports within 6 months and upwards of 12 months if there is a cruciate injury.

What will rehab involve?

Early management will include bracing of the knee, proprioception, strength and non-weight bearing cardiovascular exercise such as gentle swimming and cycling.

Longer term rehab will be dependent on the needs of your daily activities or sport requirements.

Talk to your physio about how to get you back on top of your game!

A Pain in the Neck: How does posture influence neck pain?

Neck or cervical pain is becoming increasingly common, with the highest prevalence among office and computer based workers. Physios commonly hear clients admitting to ‘bad posture’ – but do we really know what bad posture is?

Neck or cervical pain is becoming increasingly common, with the highest prevalence among office and computer based workers. Physios commonly hear clients admitting to ‘bad posture’ – but do we really know what bad posture is?

There can be many causes to neck or cervical pain, from a joint sprain, disc or nerve injury. This blog will focus on postural neck pain arising from a condition called myalgia, meaning tight, fatigued, painful muscles. This generally occurs without a history of trauma and yet is one of the most common causes of neck pain.

It is a common misconception that ‘sitting straight’ will solve all postural pain.

The neck is designed to move and although you may not realise, sitting in one position for an eight hour shift is quite a work out for your postural muscles.

Posture can have an influence on neck pain: rounded shoulders can create a forward head or chin poke posture, resulting in the muscles at the back of your neck working overtime to hold your head up. What some may not know is sitting very tall off the back of your chair can have an equally bad effect. An overly upright posture places a huge demand on the postural muscles, having a similar effect to clenching your fist for a long time – the muscles get tired and sore!

Although we aim for a ‘neutral’ posture, every body and spine is different and this ‘ideal’ posture looks different for everyone. The most important factor is finding a comfortable position, often with some low and mid back support. Having support over these areas helps ‘unclench the fist’ by offloading the postural muscles. It is important to remember that if you must be sedentary for a long period, you take breaks or change your sitting posture regularly. Neck stretches or rotations, walking to a collegue’s desk rather than emailing them or using a sit-stand desk are all ways to take a break from one sustained posture.

Studies have shown individuals with chronic neck pain (neck pain for 3 months or longer) show reduced endurance of deep stabalising muscles in the neck and have a reduced ability to maintain an upright posture. Although physiothearpists can provide hands on treatment to relieve symptoms, often the underlying cause of pain is a lack of strength and endurance of the muscles supporting the head. Manual therapy should always be paired with postural control and upper limb strengthening exercises.

Take home points:

Every spine is different, and there is not one ideal posture for everyone

Sitting in ANY posture for a prolonged time can cause pain, plus being sedentary isn’t good for our physical health

Finding a comfortable, supportive posture at work will reduce the risk of developing postural neck pain

General exercise and specific strength training for the postural muscles will increase robustness and significantly decrease the risk of neck pain

Sleep Hygiene: Simple tips to keep it clean

here is a reason we spend approximately one third of our lives sleeping. It is a very important aspect of life and affects just about every biological system of the human body in one way or another. With that in mind it is still amazing how many people still deprive themselves of it. According to the Geneva Convention, sleep deprivation can be interpreted as a form of torture. So, it begs the question, why do we knowingly do it to ourselves?

There is a reason we spend approximately one third of our lives sleeping. It is a very important aspect of life and affects just about every biological system of the human body in one way or another. With that in mind it is still amazing how many people still deprive themselves of it. According to the Geneva Convention, sleep deprivation can be interpreted as a form of torture. So, it begs the question, why do we knowingly do it to ourselves?

It has been reported that up to 45 % of Australians suffer from inadequate sleep. With 24/7 nature of life today, the time we would normally allocate to sleep is now taken up with other “more important” activities such as studying for an exam, working late to earn that promotion or just partying. As a consequence, both sleep quality and quantity are being affected which is having a bigger impact than we think on our health.

Loss of sleep affects our ability to function at optimal efficiency. It can affect physical performance such as reaction time, tissue recovery and aerobic endurance as well as cognitive performance such as alertness and ability to perform complex problem-solving tasks.

In addition to the obvious and more noticeable and immediate side effects of sleep deprivation. There are many invisible yet serious consequences that affect our immune, hormone and metabolic function. They can subsequently increase the risk of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, chronic pain disorders, developing the cold/flu and even increase the risk of sustaining sporting injuries by nearly 2-fold.

So how much sleep do i need?

Age and genetics play a key role in this. However generally:

· Infants need around 16-18 hours of sleep

· Teenagers need around 9 hours

· Adults need between 7-8 hours

Research has shown that both deprivation of sleep quantity and continuous sleep interruption (waking throughout the night) may have very similar effects. Therefore, not only getting an adequate amount of sleep is important but also sleep without regular waking is required for good sleep health.

Can I nap during the day?

Having an afternoon nap can help offset the negative effects of sleep deprivation. Research have also shown It can also have a positive effect on sporting performance although only for people who have had reduced night time sleep. Napping can be an effective way to improve sleep health. Just be mindful not to nap too late in the afternoon or for too long which may impact the quality of night time sleep. Napping/sleeping more than 30 minutes can lead to “sleep inertia” which is a physiological state where you feel less alert and drowsier when waking.

How can I achieve good sleep hygiene?

Good sleep environment

Numerous studies have shown a relaxing environment has a significant impact on sleep. A dark and quiet bedroom will help optimise sleep. Additionally, the temperature of the room can also play a big role with research showing a bedroom temperature of 18-22 degrees appears to best for a good night’s sleep. If you are still struggling to reduce external stimuli, the use of earplugs and eye masks can be helpful.

Get off the grid and unplug before bed

Limit use of devices such as phones, tablets, laptops at least 1 hour before bed. The use of these devices will make it difficult to relax prior to bed due to an increase in brain activity. Blue light also has a suppressive effect on production of the hormone melatonin which assists the body in falling asleep. If you must use a device close to bed Night Shift setting on devices or applications that filter blue light are recommended.

Avoid stimulants too close to bedtime

Avoid taking stimulants such as caffeine (within 5-8 hours before bed) and alcohol before bed. Although alcohol may seem to assist in getting to sleep faster it can actually affect the quality of sleep throughout the night

Food and drink

Avoid large meals and large quantity of fluids immediately before going to sleep. This has shown to have a negative effect on sleep. Try to aim to eat approximately 2-4 hours prior to sleep.

Have a routine

Try to have a consistent night time routine before going to bed each day. Additionally, try going to bed and waking up at the same time each day. This consistency will help regulate your body clock allowing for better quality sleep

Get out and exercise

Regular exercise is an extremely effective way to help manage stress and ensure you are tired enough to get to sleep at the end of the day.

Additionally, exposure to natural light during the day can help normalise your body clock and hormone levels and in turn assist in good sleep health.

Wind down before sleep

Try to reduce any physical, emotional and cognitive stressors. Activities that increase physical or mental alertness will make it difficult for the body to switch off when it’s time to go bed. If you are the type to have an active mind before sleeping, techniques such as mindfulness/meditation and journaling has shown to help switch off a racing mind.

FIVE questions you should ALWAYS ask your orthopaedic surgeon before making a decision on managemen

Orthopedic surgeons are indispensable members of the health profession and have a level of anatomical and biomechanical knowledge and a degree of experience that is rarely surpassed.

However, if you’ve ever been for a consultation with an orthopedic surgeon, you’ll know how fast the appointment passes. Many of our patients have reported being in-and-out without feeling like they’ve said more than 10 words.

Most consults will last 10-15 minutes and within this short space the surgeon has a certain “volume” of assessment to conduct and information they MUST deliver. It’s easy to see why they can occupy most of consultation to you leaving little opportunity for questions or express your opinion. When the opportunity finally arises, many patients are so bombarded with information that they forget the questions that had been circling in their head for days!

The surgeon is not to blame here as they are exceptionally busy individuals and with a huge demand on their limited time and wealth of knowledge and experience.

However, it makes it imperative that you use the time well and ask direct and concise questions to ensure you leave the session fully informed and able to make the decision that is best for you in your unique situation.

We decided to put together a list of questions that you should leave the consultation with the answers to. We’d recommend you print the 5 questions (and add any others you think of) and review them quickly before leaving the consultation to ensure you don’t leave with unaddressed concerns.

1. Is there any way that I can AVOID surgery and how would outcomes compare if I took this option?

ALWAYS ASK THIS QUESTION.

There is ALWAYS an alternative when it comes to surgery.

For example, considering a shoulder dislocation in a young male AFL player, a stabilisation surgery is highly recommended. Without surgery, this patient would have at least a 70% risk of the injury recurring. In contrast, with a Latarjet stabilisation he could expect as low as a 2.7% risk of recurrence.

However, you always have choices. You could try and be one of the 30% who survive non-operatively. Likewise some patients might have no desire to return to AFL and consider moving to a less “risky” sport such as triathlons where an operation is completely unnecessary. So even though we would recommend the stabilisation surgery in general, for 3 different people, they may choose 3 different options based on their own preferences.

To sum up, there is never a single option and you need to ask this question to have accurate information to allow you to weigh up the positives and negatives of all your options and make the right choice for you.

2. How long CAN it take to recover - worst case scenario? What will I feel/how painful will it be?

Yes, the problem/pathology may be fixed with surgery, but the soft tissue that is disrupted in the process will be painful and take some time to recover from. This obviously depends on the nature of the surgery but it will almost always be very painful initially.

Everyone asks how long it will take to recover. The surgeon will often tell you how long it usually takes based on average outcomes.

However, humans are complex and varied creatures, and so surgery is not like changing a part on a car.

For example, if a surgeon advises that you CAN start walking crutch-free at 7 days-post does not mean that you WILL. Some may be ready at 4 days, while some may take 14.

Many patients get disheartened because they’re running behind the timeline, or because a friend had the same procedure and was much better at this point. However, the timeline is based on the average recovery, and your friend may be an unusually high performer due to a whole host of factors such as severity of condition, genetics and specific surgical differences.

To manage these complex situations, it’s always a good option to ask the surgeon how long it CAN take and ask for the worst case scenario. It’s important to not catastrophize about this as it is an unlikely outcome, but knowing it can help prevent frustration when your’re running behind the average timeline. This also gives us a clear definition to differentiate between things are going slowly and things are going wrong.

3. Are there other ways to do this surgery? Why have we chosen this variation?

This question will get a bit technical and some may prefer not to worry about it, but there are many ways of surgically achieving your goal.

Clinical trials help provide us with some answers as to which way is the most likely to be effective, but also provide an insight as to what can go wrong.

For example, to revisit shoulder dislocations, there are two surgical approaches most commonly used: the Latarjet procedure or an arthroscopic bankart repart.

There is now a solid amount of research indicating a higher rate of return to sport and a lower rate of recurrence of dislocation with a Latarjet. However, it is also associated with a slightly higher risk of adverse effects, so the decision is not always cut-and-dry.

Similarly, with and ACL reconstruction, choice of graft (hamstring, quad, patellar etc), tunnel location, single or double bundle, nerve block used can all effect outcome. Many factors influence the surgeons decision, and they will undoubtedly offer the best solution in their opinion. While you do no need to have personal knowledge on any of the above, we think it’s a good idea to obtain this information and understand WHY they have made the decisions they have.

It’s a good idea to write this down too as the technical terms are usually hard to recall.

4. How many of these procedures do you perform a year?

There is a body of research regarding total knee replacement operations and ACL repairs that consistently associates higher yearly volume (how many a year the surgeon performs) with fewer infections, shorter procedure time, shorter hospital stays, lower rate of transfusion, and better outcomes in the long-term. Research on other procedures is less available, but it’s safe to extrapolate that experience matters, just like any other profession.

If the surgeon has a relatively low yearly volume, it doesn’t mean that they will do a bad job as they will have undergone may procedures in their training and education.

Likewise, certain procedures as less commonly performed (e.g. repair of a complex bone break) so a high yearly volume is not feasible.

In any case, it’s worth asking how often they perform the procedure. If they perform a low number annually (<10 on a common procedure such as TKR), you could consider politely inquire if they have colleagues that specialize in this procedure and perform it more often.

With something as serious as a surgical procedure, you are always entitled to a second opinion. A good surgeon will have the self-awareness to know when they are and are not the right person for the job. If they can confidently assure you they have the necessary skill-set and experience, then you leave the consult knowing you are in safe hands.

5. Always ask YOURSELF, do I understand the diagnosis and/or the proposed solution? Test this by trying to summarize the information to you surgeon before you leave.

It’s a simple place to finish but make sure you fully understand what your surgeon has told you in the first place as errors in communication are so common in this situation.

The true test of this comes when you go home and try the “family/friend test”. If you can explain your problem well to family/friends, then you probably took the information in effectively. However, if it makes perfect sense in your head at the time, but you struggle to explain it later then you may not have understood it as well as you thought.

To ensure you pass the” family/friends test’, I recommend people try and perform a summary at the end of their consult, e.g.:

“So, if I understand correctly, my problem is that……and the proposed solution would fix this by…….all going well I should expect……but it may take as long as……..”.

This way, your surgeon will be able to highlight and correct anything that got lost in translation on the first occasion.

Conclusion:

There you have it – five important questions you should always ask in a consultation with an orthopedic surgeon. Any situation that requires the consideration of surgery is bound to be complex so it’s imperative that you get all the information. These five questions will help keep you focused and ensure you get the information needed to make a fully-informed decision that is right for you and your set of circumstances

PREHAB: TAKING CONTROL OF YOUR RECOVERY

Optimising recovery from surgery:

Regardless of what it’s for, surgery can be scary and overwhelming. It is normal to feel a sense of helplessness or feeling as if you don’t have control over the end outcome. However, it is important to understand that you play the single most important role in the outcome of your recovery and it starts long before you meet with your surgeon. Preparing your body and mind for what you are about to encounter is an important aspect of recovery and creates good habits for your post-surgery rehabilitation.

How do you do this, you ask?

We call this Prehab

Prehab is a programme designed to prevent injuries before they actually occur. This can be applied to anyone or any injury however in the context of surgery it is you taking an active approach to prepare yourself physically and mentally for what you are about to go through. It plays a massive part in giving you the power to control the success of your upcoming surgery.

Why should you do Prehab?

Numerous studies have shown that patients who participate in Prehab have significantly better outcomes than those who do not. Those who undergo prehab generally have quicker recovery times, return to sport faster, have less complications and are generally more satisfied with their end outcome.

Does this apply to me?

Prehab is highly recommended for anyone planning to undertake or has been referred for surgery. Research has shown Prehab to be effective in enhancing recovery for patients undergoing total hip and knee replacements, ACL reconstructions, shoulder surgery such as rotator cuff repairs and lower back surgery.

What does it involve and how long for?

Ideally, undergoing 6-12 weeks of Prehab prior to surgery will optimise post-surgical outcomes. In most situations this is not possible due to availability with your surgeon. This does not mean that Prehab won’t help be helpful for you. As they say, something is better than nothing and there are still many meaningful benefits to be gained with only 2 weeks of preparation.

5 reasons to Prehab:

1. Get control of your pain:

A prehab program should give you the tools to minimise pain. Reducing pain early will enable normal muscle activity and put you in a good head space leading up to surgery.

2. Get in optimal physical shape:

Through a specific exercise program, you can improve muscle strength, flexibility, balance and coordination which has shown to optimise and speed up the recovery process post-surgery. Additionally, improving general fitness and wellbeing has many added benefits such as weight loss and improving mental resilience which is extremely important to recovery.

3. Create good habits and kick the bad habits

Firstly, creating good habits beforehand will make your life so much easier once you have been discharged from hospital. Good habits start with getting in a healthy exercise regime This extends to healthy sleep, nutrition and lifestyle habits which your physiotherapist and health practitioners can guide you on.

Conversely, bad habits will have the opposite effect, so you can imagine the importance in changing these prior to surgery.

4. Manage anxiety/stress

It is completely normal to feel anxious or stressed prior to surgery. In addition to physically preparing yourself you must also get yourself in the right headspace. Prehab will help mentally prepare you by getting you in a good mindset for the upcoming rehabilitation process. It will also teach you appropriate coping strategies to deal with pain and stress associated with the injury.

5. Speed up your recovery and reduce post-operative complications

Prehab sets you up for a successful recovery leading to quicker recovery and return to sport times. It also reduces the risk of common complications associated with surgery.

Please feel free to contact our team at East Vic Park Physio on 9361 3777 if you have any questions or would like to find out if Prehab is appropriate for you.

Tennis Elbow: Getting to Grips with the issue

About:

Tennis elbow is a very common term used to describe lateral elbow pain. However, people can experience the condition without having ever picked up a racquet. The most up to date term currently is lateral epicondylalgia (LE) with “algia” meaning pain. This reflects the general shift away from it being considered an inflammatory condition in which the tendons around the elbow are inflamed. Rather, it is thought that the tendons become overloaded and sensitisation of the area occurs causing a heightened pain response that in turn causes inhibition of the muscles in the forearm. Inhibition results in a decrease in muscle “strength” which means everyday tasks like lifting a kettle become harder and tend to overload the tendons further causing more pain which causes more inhibition etc. (a vicious cycle of pain).

Even though the area of pain is usually focused around the outside of the elbow, it is actually the tendons of the forearm and wrist muscles that are affected. They come from a common origin point which attaches to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus bone. The implications of these tendons/muscles being affected is that it is mainly wrist and hand movements (e.g. gripping and lifting) and not elbow movements that are most painful.

Usually tendon pain occurs either through an acute injury or abnormal loading of the tendon (e.g. awkward tennis swing or a repetitive task at work). However, LE can also occur with no specific trigger. Around 40% of people will experience some form of LE in their lifetime and it is most prevalent those aged from 35-54 years (Bisset & Vicenzino, 2015). Regardless of the cause, it can be treated successfully to return the sufferer to full function. This will usually involve a loading program for the tendons to gradually improve their capacity and to “re-strengthen” the muscles. Rest alone does not address the muscle weakness or drop in capacity and this results in prolonging the injury. Weakness around the shoulder blade and shoulder muscles also needs to be addressed as the elbow can be the point of compensation for those areas further up the chain.

Common presentation:

· Pain in the lateral elbow or into the forearm

· Pain with tasks like lifting and gripping

· Weakness with tasks like lifting and gripping

General advice:

· Ice over the painful area (usually lateral elbow)

· Massage the forearm muscles (NOT the lateral elbow)

· Avoid poking or prodding the painful area (feels good at the time but really tends to make it worse)

· Use of a brace or taping around the upper forearm

· Avoid aggravating activities

· See your physiotherapist for a gradual loading program

· See your physiotherapist for an upper limb strengthening program

It is always best to be assessed by a physiotherapist to ascertain a correct diagnosis so you can receive the best treatment possible for your specific condition. Here at East Vic Park Physiotherapy, our physiotherapists are very experienced in assessing and treating lateral elbow pain. Click the link at the top of the webpage to book an appointment or call us on 9361 3777.

References:

1. Physiotherapy management of lateral epicondylalgia. Bisset, L & Vicenzino, B. 2015. Journal of physiotherapy (61), 174-181.

AC Joint pain - The "Other" Shoulder Pain

Anatomy

The Acromioclavicular (AC) joint is located at the lateral tip of the shoulder. The joint is formed by two bones, the clavicle (collarbone) and the acromion (a portion of the scapula/shoulder blade). In between the joint sits a fibrocartilage meniscal disc and the bones are connected by a number of ligaments, muscles and a joint capsule.

Role

The AC joint acts as a pivot point in the shoulder allowing the shoulder blade to rotate as the arm is lifted upwards. If it is dysfunctional it affects the control of your shoulder.

About

The AC joint is very commonly injured in contact sports that involve tackling like rugby or AFL. This is classified as a traumatic injury in which the ligaments can be torn and the capsule disrupted which results in the bone separating. However, you can also have AC joint pain from overloading the joint or degeneration of the fibrocartilage meniscus. It can also develop into a condition called osteolysis which is quite common in gym goers.

Differentiation from “bursitis” or impingement (common shoulder pain)

Shoulder bursitis/impingement is a very common condition in which the bursa and tendons in the shoulder get inflamed or overloaded. Often a cortisone injection is prescribed which can reduce the pain if the bursa is the main issue. However, if it is not the correct diagnosis then ongoing pain and disability can perpetuate. It is very important to get your shoulder assessed by a physiotherapist to differentiate between the two conditions so the right treatment plan can be selected. Please note that Impingement CAN occur as a result of AC joint pain or injury but is not the primary diagnosis.

Common presentation

· Pain at the top or tip of the shoulder

· Difficulty lying on the shoulder

· Difficulty bringing the arm across the body

· Pain with lifting an object above your head

· Pain with gym activities like bench press

General advice

· Try icing the area especially when it is painful

· Rubbing voltaren gel on the area can help reduce pain, the joint is superficial enough for the gel to have some effect

· Applying taping to pull the shoulder upwards can take the pressure off the joint and relieve discomfort

· A structured rehab program is helpful in making the muscles around the joint stronger so there is less load on the area

· A cortisone injection can be helpful if conservative treatment isn’t effective, as long as they inject the right spot

· Most importantly, visit your highly trained physiotherapist for a thorough assessment and in-depth treatment plan

THE IMPORTANCE OF MUSCULOSKELETAL SCREENING

Finals time for most winter sports is fast approaching and from a physiotherapy perspective this is the time of year that we see a spike in sporting injuries. A lot of these injuries tend to be to parts of the body that have some sort of deficit, be it strength, length or control. It is quite hard to be able to identify these areas yourself and even physiotherapists would find it hard to accurate identify these deficits purely through observation.

Finals time for most winter sports is fast approaching and from a physiotherapy perspective this is the time of year that we see a spike in sporting injuries. A lot of these injuries tend to be to parts of the body that have some sort of deficit, be it strength, length or control. It is quite hard to be able to identify these areas yourself and even physiotherapists would find it hard to accurate identify these deficits purely through observation.

This is why screening is so widely utilised for athletes from amateur to elite. Screening usually involves a battery of tests that give objective measurements that are then compared to the normal values for an athlete in a specific sport. Screening can also involve questionnaires that focus on general health and previous injury history.

An article by Sanders, Blackburn and Boucher (2013), looked at the use of pre-participation physicals (PPE) for athletic participation. They found PPE’s to be useful, comprehensive and cost effective. They explained that PPE’s can be modified to meet the major objectives of identification of athletes at risk.

An article by Maffey and Emery (2006) looked at the ability of pre-participation examinations to contribute to identifying risk factors for injury. They found limited evidence for examinations in terms of the ability to reduce injury rates among athletes. However, they were effective in the identification of previous injury (such as ankle sprains) and providing appropriate prevention strategies (such as balance training). From this it has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent injury. It may also be useful in identifying known risk factors which can be addressed by specific injury prevention interventions.

An example of a screening measure that is typically used in screening protocols includes a knee to wall test (KTW). This test is used for ankle dorsiflexion as well as soleus muscle length (one of your calf muscles). The test is performed using a ruler which is placed perpendicular to a wall with no skirting board. The athlete puts their foot flat on the ground next to the ruler and as far from the wall as possible as long as their knee is touching the wall. Distance from the wall to the end of the big toe is noted by looking at the ruler. An example of a normal distance for netball players is greater than 15cm on each side.

Here at East Vic Park Physiotherapy we have developed a number of specific musculoskeletal screens for a variety of sports including netball, running, swimming and throwing sports. They comprehensively identify the key risk factors that are seen in injuries sustained in each sport. If you are interested in preventing injury for the upcoming sports season, then contact the clinic on 9361 3777 and book your screening appointment today!

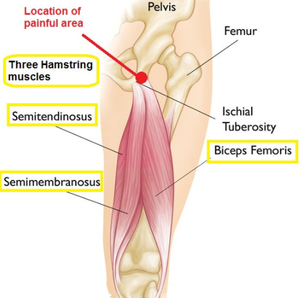

Proximal (High) Hamstring tendinopathy – A Real Pain in the Bum

The hamstring consists of three muscles and it has a very important role in extending the hip from a bent position, e.g. initial phase of a deadlift, and in bending the knee, e.g. at the end of leg swing while running. While this muscle group is a very common source of problems, most commonly tearing when sprinting, this usually occurs in the middle of the muscle belly. In contrast, proximal hamstring tendinopathy refers to a reactive painful hamstring tendon at its attachment point on the base of the sit bone (ischium). This is why it is call a high hamstring tendinopathy.

Tendinopathy in the hamstrings is common in athletes, particularly in sports that involve large periods of time bent forwards, such as hockey, or involving high driving of the knees, such as sprinting or hurdling. However, it is often seen in other populations also., such as runners and even in the elderly.

How does it happen?

The hamstring tendon runs very close to the sit bone and is protected from compression and friction by the ischial bursa. If you gradually increase your training over time, these protective structures adapt providing greater protection. However, with sudden increases in the volume of compression on the tendon, this protection may not be sufficient, leading the tendon become extremely reactive and irritable. Sudden increases in compression can come from an increase in any of the following:

Direct compression from an external source, e.g. prolonged periods of sitting, especially on hard surfaces.

· Extreme positions of hip flexion pull the tendon tight against the sit bones, e.g. pulling knee close to chest, deep squats.

· Any hamstring stretch will likely compress the hamstring against the sit bone

· Contraction of the hamstring while already in a position of stretch will pull it tighter against the bone and increase the compressive forces, e.g. hurdling, sprinting (below)

Figure 1: Examples of positions of stretch with strong hamstring contractions that cause large volumes of compression of the hamstring tendon

It is important to again note that these compressive forces are normal for the hamstring. It is usually sudden changes in the volume of compression that is the problem, rather than compression itself.

The typical presentation is a deep ache or burning sensation right on their sit bone. It is usually quite focal but can sometimes radiate down the posterior thigh. Symptoms typically develop gradually over time, often without any clear moment of injury. They are usually worsened during activities involving hip flexion, hamstring stretch and hamstring contraction, particularly if all three are combined such as when lunging, squatting, sprinting, hurdling. Running up hills or stairs is usually worse than running down. Early on, the pain is usually worse at the beginning of activity, but warms up and gets better during activity, only to be very sore afterwards and the next morning. As it progresses and becomes more severe, it can worsen into activity and be quite painful even at rest.

What else could it be?

The anatomy in the area is complex and several other diagnoses should be clinically investigated and ruled unlikely before settling on a diagnosis of hamstring tendinopathy. The piriformis (circled in green) and deep gluteal muscles below it run close by and can develop tendon pain. The sciatic nerve (thick yellow band) also runs through this region and can become entrapped and irritated. Further, pain from the lumbar spine (lower back) and sacroiliac joint (where the pelvis meets the spine) commonly radiate into the buttock region and should always be screened for. In rarer cases, the shaft or the outside of the femur can impinge against the ischium causing irritation.

A comprehensive clinical assessment is usually sufficient to evaluate the likelihood of these various diagnoses and develop a comprehensive treatment strategy. In some cases, further imaging or referral to a specialist sports physician may be necessary.

How do I manage it?

1. Avoid compression – don’t stretch it!!

In the early stages, avoiding compression is the best way of settling symptoms in the early stages. Seating should be improvised or special cushions can be ordered to take pressure off the sit bones. Moreover, having a large glute bulk can provide extra protection. Static glute contractions can ease pain while sitting, and building glute bulk over time can be a useful strategy.

Avoid deep flexion exercises (such as squats or lunges), hamstring stretching and exercises that contract the hamstrings at long lengths such as stiff legged deadlifts or arabesques.

Later in rehab, once the tendon has settled down and is less irritable, then it is important to gradually add compressive activities back in to ensure full restoration of function. Your physio will again guide you through this process as it becomes appropriate.

2. Load management

For athletes, the hardest part is getting the balance right. This condition can be hard to manage if you continue to train at your usual level and you may be required to reduce or at least modify your workload. Typically, we are happy for our athletes to continue some volume of training with the condition so long as the pain is tolerable and doesn’t worsen from week to week. Use a consistent exercise performed at the same time every week to monitor weekly progress. If this is increasing, more modification may be necessary. However, if it is stable or decreasing than the current level is acceptable.

Activities such as sprinting, hockey, rowing, or uphill running are more provocative. We try to limit these activities to 2 times per week to allow sufficient recovery time between sessions. Outside of this, cross training is recommended to improve fitness without further irritating the hamstring tendon. We suggest aqua-jogging, swimming, cross-trainer, upright cycling with a well fitted seat height.

3. Hamstring strength exercises

Lower limb tendinopathies respond very well to exercise and we have found similar results in hamstring tendinopathies by strengthening the hamstring itself. The trick is to get the right exercise for the right person at the right time. The best way is to get a specific rehabilitation program from your physiotherapist. They can guide you on which exercise to do at each stage and how many sets/reps/frequencies to ensure you get the best-fit dosage for your condition at its specific stage.

4. Biomechanics

Certain characteristics may put someone at an increased risk of developing a hamstring tendinopathy. For example, having a very stiff lower back, or tight hip flexors will pull your hips into a forward tilt. This means that while running, your hamstrings will be on a higher stretch throughout. Addressing these biomechanical factors can be very useful in reducing symptoms during activities and preventing reoccurrence.

What else can I do?

· Dry Needling and Soft Tissue Mobilisation

A tendon that does not like compression is unlikely to respond positively to pressing on it or sticking needles in it. However, soft tissue work can provide effective pain-relief if directly at highly toned muscles surrounding the irritable tendon, such as the hamstring muscle belly, or deep gluteals. Likewise, soft tissue work may be useful to help address some of the biomechanical deficits mentioned above, such as releasing the lower back or hip flexors.

· Anti-inflammatories

Anti-inflammatories such as ibruprofen can be useful to settle the pain in hamstring tendinopathies, particularly if caught early and applied stringently over a short period. We would suggest visiting your physician before trying this approach. It is important to couple this approach with comprehensive rehabilitation to ensure full restoration of hamstring function and reduce the risk of reoccurrence.

· Injection

Corticosteroid may provide some short-term relief (approximately 6 weeks). However, symptoms tend to reoccur once the effects of the injection have worn off. Serial injecting is unwise as some evidence suggests it may cause deterioration of the quality of the tendon and worse outcomes. Corticosteroid should be used only with careful consideration after exhausting other management strategies.

PRP injections have been suggested to improve tissue healing. However, the currently available evidence does not support the use of this strategy, as it has a low likelihood of being any more successful than placebo.

· Shockwave therapy

Shockwave therapy has shown some promise, albeit with mixed results, in the treatment of lower limb tendinopathy. In our experience, it may lead to worsening of symptoms in irritable, acute tendinopathies. However, it can be a useful strategy in some patients, particularly those with more chronic and less irritable tendinopathies.

· Surgical management

Surgical procedures have been described but should be an absolute last resort for the management of hamstring tendinopathies and only used when all other strategies have failed.

Plantar fasciitis

WHAT IS IT?

Plantar fasciitis Is a very common cause of heel pain. It can be quite debilitating and can last for months if not addressed. Typically, pain will be felt on the inside of the heel and arch. Pain can be sharp or achy. There can be a small amount of swelling over the medial heel as well as tenderness to touch. Mornings are worse, with it usually taking anywhere from 2-3 minutes to an hour for the stiffness and pain to reduce.

POSSIBLE CAUSES

· Change in load eg Running/jumping

· Change in footwear

· Change in activity surface eg. Hard surface

· Acute trauma eg. Stepping on a rock

SCANS

Sometimes your GP will refer you for a scan of the affected area. Most likely it will be an x-ray or an ultrasound. This may show that there are heel spurs or “tears” in the plantar fascia. Although it can be good to confirm the diagnosis, scans can sometimes be detrimental as it may cause people to become worried about their condition. Scan results can also correlate poorly with symptoms an example being that people with heel spurs on x-ray don’t necessarily develop Plantar fasciitis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

· Soft tissue release

· Joint mobilisations

· Taping techniques

· Orthotics

· Exercise program (Physiotherapist prescribed)

· Load management plan (Physiotherapist prescribed)

LOAD MANAGEMENT

Load management is about controlling how much you use the particularly area on a day to day basis. Usually when an area becomes painful, its load capacity (ability to tolerate load) is reduced so it becomes overloaded quicker than normal. This means that even normal tasks or activities like walking or standing can cause it to become more painful and swollen.

One of the ways to improve the capacity is to progressively build up the amount that you use that area. This can be done with a specific structured exercise program (physiotherapist prescribed) that is made more difficult over a period of time. It is normal for rehabilitation to be painful, you cannot improve load tolerance without causing some discomfort.

The best way to monitor improvement is by recording morning pain (rating it out of 10, 10 is worst, 0 is nothing). It is normal to have ongoing morning stiffness even after pain has completely disappeared.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sometimes Plantar fasciitis might not be the cause of heel or foot pain. It is important to see a physiotherapist to get an accurate diagnosis. Other causes of heel pain are below:

· Plantar or Calcaneal Nerve pain

· S1 radiculopathy

· Stress fracture

· Tarsal tunnel syndrome

· Fractures

· Retrocalcaneal bursitis

· Spondyloarthropathies

· Cancer (osteoid osteoma)

TIPS FOR PAIN FLARE UPS

· Try to avoid walking around in bare feet

· Using ice over the sore area can give temporary relief

· Stretching it may be uncomfortable so roll a golf ball/tennis ball under the foot instead to release tight muscles

· Pain relief or anti-inflammatory medication can be helpful but ask your pharmacist for advice

· See your physiotherapist for a progressive loading program

Groin Pain

As pre-season training gets underway for winter sports codes we generally see an increase in the number of patients with groin pain presenting to our clinic. Discussing groin pain as a whole is a very large topic, so for the purposes of this blog I will discuss non-traumatic groin pain and in particular the most common factors that can lead to injury.

Non-traumatic groin injuries are typically complex and require a thorough assessment to determine the factors that have led to the injury and a comprehensive exercise rehabilitation program to recondition the athlete to be ready to return to their sport.

WHAT IS IT?

Groin pain is an umbrella term for pain felt in the groin area. It is not diagnostic and does not indicate a specific pathology or tissue(s) affected. Groin pain can be sub-grouped into 6 different areas:

· Adductor related

· Hip flexor (iliopsoas) related

· Abdominal (inguinal) related

· Pubic related

· Hip joint related

· Other (neural, referred pain, fractures, abdominal/gynaecological conditions etc)

It is common more than one of these sub-groups to be affected and insufficiencies in one area can lead to an overload in another.

WHY DOES IT OCCUR?

Three common reasons for the development of groin pain in sporting people include training errors, poor mechanics and age.

· Training errors causing injury usually refers to “too much too fast” and is usually seen with athletes rapidly increasing their training amounts without adequate recovery between sessions causing a progressive overload of structures in the groin area. Groin pain will commonly present as preseason training reaches 3-4 weeks in and more commonly as running demands transition into higher amounts of sprinting and agility.

· Poor mechanics refers to muscle imbalances, poor movement control and patterns, poor posture, inadequate strength, lack of flexibility and sub-optimal technique for sport specific skill. This is where a good sports physiotherapist will be able to conduct a comprehensive assessment to determine which of these factors are contributing to your groin pain.

· Younger athletes are more susceptible to developing groin pain as their skeletal system is less mature to withstand the stress that training can put on the body compared to older athletes (25+ years).

MANAGEMENT

The pain will generally settle with a combination of rest and anti-inflammatory medication. During this rest period it is important to address the factors that have led to developing groin pain (poor mechanics) to avoid reaggravating the injury when you return to running. It is very important to have a graduated return to running plan in place to allow for optimal recovery between sessions and avoiding too much load too soon.

PREVENTION

The old adage “prevention is the best cure” is applicable for groin pain and there is plenty that can be done to prevent it. If you have had groin pain in the past, having a preseason screen with your physiotherapist is beneficial to assess if any predisposing factors are present. A comprehensive strength and conditioning program to address any factors as well as condition your body to tolerate the training loads can help prevent groin injuries. Also making sure to optimise your recovery between sessions – for helpful tips read our blogs on recovery – will help prevent the development of groin pain.

Shin Pain and Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome - An Update

Is there an answer or should I toughen up and suffer in silence?

Preseason is a common time for overuse injuries and pain to present due to the sudden increases in training volume and intensity. Shin splints is one such injury, which seems to just get worse and worse. Often this problem plagues the athlete annually at this time of year. Occasionally it persists into the season to the point where the athlete is constantly playing through pain, suffering post-game and performances can begin to be affected. Since they haven’t had an “injury”, the athlete often feels like they just need to toughen up, push on through and it will pass. However, the problems seem to only get worse and worse the harder they push. Other athletes take time off and are increasingly frustrated to find the injury returns as soon as they get back to business.

So what is shin splints and what causes it?

Shin splints is actually a loose term because it encompasses a range of presentations, including stress fractures and compartment syndrome. It is still widely used but an attempt is being made to oust it. You may or may not have heard your physio refer to it as medial tibial stress syndrome. Medial tibial refers to the inside of the lower shin where symptoms are most frequently reported. Stress syndrome simply indicates that relative overuse is most commonly the cause.

As the narrowest part of the tibia, tiny bending movements occur at this site when running. This causes microscopic breakdown of the bone. There can also be breakdown of the connective tissue that encapsulates the deep muscles of the calf, where it attaches to the bone at this location. However, this is a normal process that occurs in everyone every time they go for a run. The strength of the original tissue and the amount and intensity of the running determines how much breakdown occurs.

Our bodies respond well and adapt to training. Our immune system will usually kick in pretty quickly to clean up the breakdown and lay down new bone and connective tissue in its place. As seen in the picture below, given proper loading volumes and recovery time, our bones overcompensate each time to get thicker, denser and stronger. This means that we can tolerate increasingly difficult challenges. This is a very similar process to how you can build muscle in the gym. However, bone does take a longer to recover, and longer to grow than muscle, but is just as plastic and adaptable.

From "How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Council consensus statement on load in sport and injury risk" by Soligard et al. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016: 50:1030.

How do I know how much is too much?

This varies greatly from person to person and is dependent of a number of factors.

Loading spikes:

We know that strong bones better resist breakdown and we know that bones get stronger over time. However, if you suddenly increase your training volume, frequency or intensity, you may not have time to sufficiently develop the bony adaptions necessary. Sometimes even changing mode of training to something very taxing on the calf muscles, such as hill running or skipping, is enough of overload the capacity of the tibia. Consistency and gradual increases in training load are imperative to avoid loading spikes.

Strength

Muscles develop at a different rate to bones. Importantly, muscle size is consistently associated with bone size and strength. This means bigger muscles are usually attached to stronger bones. Resistance exercises had been shown to increase bone density. Therefore, calf strengthening exercises can be useful in increasing the strength and size of the tibia so that less breakdown occurs.

Type of Runner

There are two extremes on a spectrum here. There is the athlete with calf and Achilles tendons like Pogo sticks. They often may be lacking in shock absorption and propulsion elsewhere. Naturally, if this is their primary source of power, it will also be the first area to overload. These athletes can often benefit from addressing the weaknesses elsewhere, reducing the demand on the calf muscles.

The other end of this spectrum is the athlete that has weak calf muscles, and is often knee dominant and heavy footed. A change in loading where calf strength is necessary can expose this weakness and cause overloading. Running retraining, and calf strengthening can work well in this population.

Nutrition and Bone Health:

Some people are genetically more vulnerable to low bone density. A family history of osteoporosis or stress fractures may hint at this as a factor. Another key issue is diet. We all know calcium is good for bones but vitamin D is also essential. Under-eating often occurs unintentionally, but when diet is compared with the massive energy requirements of greater than 5 sessions a week, calorie intake often becomes insufficient to meet energy expenditure. Nutrition is key to good bone health, and you can’t outrun a bad diet.

Pain Threshold

Pain is a protective mechanism, like a car theft alarm. It is designed to go off early and loudly before any substantial damage. This is a warning that there may be something to address. However, this threshold is very adjustable and dependent upon a multitude of factors. For example, the local nerve fibers become increasingly irritated and easier to set off when they are repeatedly overloaded. The red line in the picture above moves upwards and so it takes less to set it off. Like a car alarm that goes off in the middle of the night, it seems to get louder and louder.

We also know that lifestyle factors like getting poor sleep, feeling run down, stress, anxiety etc. can lower your overall pain threshold in the absence of pain or injury. In this instance, it takes much less breakdown to fire a pain response. Here, it is vital to address any of these factors that are modifiable to reconfigure the pain threshold to a more reasonable level.

Can the bone fracture?

The overwhelming majority of cases of medial tibial stress syndrome do not lead to stress fractures. This is because the rate of repair and breakdown usually meet an equilibrium long before the integrity of the bone is compromised. However, in some isolated incidences bone stress fractures can occur but this is rare. The pattern of pain with stress fractures is different from medial tibial stress syndrome. If you are concerned about developing a stress fracture, your physiotherapist can quickly establish the likelihood of it.

How do I know if I have medial tibial stress syndrome?

The common description of pain, is a dull diffuse ache along the inside of the shin. It will usually extend at least 5cm along the middle of bottom third of the shin. This pain comes on the beginning of exercise, but will often “warm up” and be less prominent as the exercise continues. As the local tissue becomes more irritated, it will last longer into exercise and may begin to even cause pain after exercise when walking or going up and down stairs. It is not limited to runners, and is very common in footie, soccer, hockey, netball and other field sports.

How long will it take to get better?

Compression garments, massage, dry needling, taping and shoe inserts may offer some short term relief. However, the results are mixed and often require trial-and-error to determine what works for that individual. They won’t solve the problem but can get you through the pain for long enough to successfully adapt.

There is great potential for long-term success the causing and contributing factors are identified and addressed. It can take time to build up the muscular, tendon and bone capacity. Likewise, the nervous system can take some time to cool down, especially the longer it has been wound up. Until then, a certain amount of patience is required. This carefully measured approach is the best way to ensure the problem doesn’t continue to spiral and progress.

What can I do for my shin pain?

1. Catch it as early as possible before it becomes increasingly irritated.

2. Start a training diary to get an idea of how much you are doing and how consistently you are training.

3. Address lifestyle factors if they are modifiable, such as diet, sleep and stress – obviously, this is not always possible!!

4. Visit a physiotherapist to identify your personal contributing factors and develop a management plan – there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Low Back Pain

Approximately 80% of people will experience lower back pain at some stage in their life. It is one of the most common reasons for people missing work and seeing a doctor or physiotherapist. Although it is extremely common it can often a bit of an unknown to the general public as to what is the cause for their pain and disability.

There are many different causes of low back pain from strains/sprains, posture related pain and overuse injuries. This blog post will mainly focus on acute strains or sprains of the low back.

Similar to other joints around the body, strains or sprains to the low back occur when a stress is placed on a tissue that exceeds what it is capable of handling. An example of this could be someone bending over to lift a heavy object off the floor. However, a heavy force is not always required to strain the back. Repetitive movements of small force can also do this.

Again like other joints around the body, different structures around that area can be irritated or strained. For the low back this can be surrounding muscles, ligaments, facet joints, discs or a combination of a few structures.

Timeframes of recovery will vary depending on what structures are involved, the severity of the injury, the demand of the person and lifestyle factors such as sleep, stress levels, diet ect.

What Can I do?

The back responds very well to movement. It is encouraged to continue to keep moving within your pain limitations. Identify positions and movements your back feels better with adopt these positions rather than the painful ones. This will differ from person to person so your physiotherapist will go over these particular activities/positions with you.

What can’t I do?

Your pain and symptoms will often be exacerbated immediately during specific activities. However, an increase in symptoms can often be noticed after completing particular tasks or even the following morning/day.

It is important to identify these activities or postures and avoid over repetition of them or prolonged time spent in those positions. These activities are often simple tasks we complete on a regular basis throughout the day so it is often unrealistic to completely avoid them. Instead, modifying how we complete them or limiting how much of them we do of them will be more effective. Eg sitting posture or length of time spent sitting.

Do I need a scan?

The majority of back injuries do not require any scans or imagining and will resolve without the need for a scan. Scans can also be misleading at times as they tend to show everything that is happening in your back even when it’s not the source of your pain. Scan results can make people anxious, worried and stressed which can make their pain significantly worse.

Imaging of the low back is potentially required when treatment/management of the injury could potentially change depending on the diagnosis or extent of the injury. Your GP or physiotherapist will discuss with you if they think imaging is required in your case.

Do I need surgery?

Again, like imaging most low back injuries do not require surgery. However, there are circumstances where surgery may be required or beneficial in addressing certain injuries. Obviously there are risks when any surgery is performed and so they are only recommended when they are truly needed.

When can I return to exercise?

This is a difficult question to answer as it will depend on a number of factors including the type of exercise you are attempting to return back to, the severity of the injury and previous injury history. However, in general, most soft tissue injuries have a recovery timeline of about 4-6 weeks. There will often still be things you will be able to do during your rehabilitation. This will usually start off with activities that do not exacerbate symptoms followed by modified versions of more complicated tasks with the aim to progress back to your previous level of function.

Will this injury reoccur?

Like most injuries there is always a risk it re-aggravating Your treating physiotherapist will advise you on ways to best prevent this from happening. This will often involve an exercise program to address any deficiencies and optimising technique and posture with specific tasks/activities.

Wrist and Hand Injuries

We use our hands repeatedly every day so it’s not surprising that sometimes we develop pain and discomfort in our fingers, wrists and forearms. Injuries in the wrist and hand can be caused due to traumatic events (e.g. a fall on an outstretched hand) or overuse, repetitive activities (e.g. computer use, racquet sports).

Anatomy

We use our hands repeatedly every day so it’s not surprising that sometimes we develop pain and discomfort in our fingers, wrists and forearms. Injuries in the wrist and hand can be caused due to traumatic events (e.g. a fall on an outstretched hand) or overuse, repetitive activities (e.g. computer use, racquet sports).

ANATOMY

The wrist and hand complex is made up of 27 bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, nerves and blood vessels. Damage to any of these structures can cause pain and can affect your ability to use your hands effectively.

COMMON WRIST AND HAND INJURIES INCLUDE:

· Fractures

· Tendon pathologies e.g. Mallet finger, De Quervain’s Disease

· Ligament injuries e.g. sprains

· Joint inflammation

· Nerve entrapments e.g. Carpal tunnel syndrome

· Arthritic conditions

· Ganglion cysts

If hand and wrist injuries are not assessed and treated properly this may lead to further impairments in the future.

EARLY MANAGEMENT

Should include rest, ice, compression and elevation (RICE principle) for the first 48-72 hours. Anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS) also have a role in early management, taken in the form of tablets and topical gels.

PHYSIOTHERAPY

Your physiotherapist will go through a comprehensive assessment to determine the source of your pain. Once the source of your pain has been established the initial aim of treatment includes education and addressing acute symptoms (pain, lack of movement and loss of strength).

When indicated your physiotherapist will start to address other issues such as loading, muscle imbalances, poor posture and biomechanics.

PREVENTION

To reduce the risk of recurring wrist and hand injuries it is important to maintain adequate strength and length of the muscles around the wrist joint.

Your physiotherapist will advise you in activities that should be avoided to decrease irritation.

RETURN TO SPORT

When returning to sport it is essential that you discuss this with your physiotherapist. Your abilities will be assessed through a series of tests to determine whether you are ready to return to pre-injury activities and/or sport.

UNDERSTANDING PAIN

An excellent video on what our understanding of pain currently is and in particular the complexities of chronic pain.

SPORTS INJURY MANAGEMENT SEMINAR

Whether your sports season is heading into finals or you are about to start gearing up for the summer season ahead, the information presented will help you to perform at your best.

a FREE seminar on sports injury management presented by the Physiotherapists at East Vic Park Physiotherapy. Topics will include muscle contusion (corkie) management, post-game recovery and a practical session on strapping.

Whether your sports season is heading into finals or you are about to start gearing up for the summer season ahead, the information presented will help you to perform at your best.

Appropriate for all athletes, parents, trainers and coaches.

Food will be provided - let us know if you have any dietary requests.

Spaces are limited so call us on 9361 3777 to secure your place now.